Strategy Pattern

In object-oriented programming languages like Java or C#, there is the very popular Strategy Pattern.

The Strategy Pattern consists of injecting “strategies” into a class that will consume them. These “strategies” are classes that provide a set of methods with a specific behavior that the consuming class needs. The purpose of this pattern is to offer versatility by allowing these behaviors to be modified, extended, or replaced without changing the class that consumes them. To achieve this, the consumer is composed of interfaces that define the behavior to be consumed, and at some point (typically during instantiation), the infrastructure injects concrete implementations of these interfaces into the consumer.

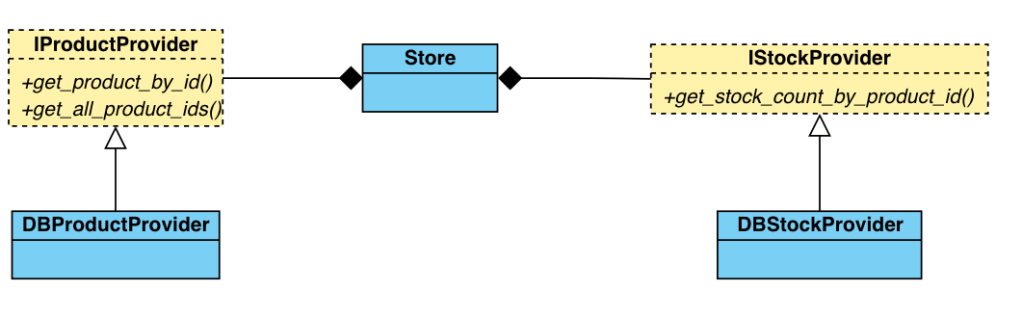

This is the example that will be used in this post: A store needs a product provider and a stock provider to gather all the information it requires.

Using the Strategy Pattern, the class diagram for the example is shown below:

In C++ the implementation of this pattern is similar to the one described here: The “interfaces” (implemented as Abstract Base Classes in C++) IProductProvider and IStockProvider and their data classes and structs will be declared as follows:

struct Product

{

std::string id;

std::string name;

std::string brand;

};

class IProductProvider

{

public:

virtual ~IProductProvider() = default;

virtual std::shared_ptr<Product> get_product_by_id(const std::string& id) const = 0;

virtual std::vector<std::string> get_all_product_ids() const = 0;

};

struct Stock final

{

std::string product_id;

int count;

};

class IStockProvider

{

public:

virtual ~IStockProvider() = default;

virtual int get_stock_count_by_product_id(const std::string& id) const = 0;

};

Now, the following code shows the service class that uses both providers, implementing the Strategy Pattern:

struct ProductAndStock final

{

std::shared_ptr<Product> product;

int stock_count;

};

class Store

{

std::unique_ptr<IProductProvider> _product_provider;

std::unique_ptr<IStockProvider> _stock_provider;

public:

Store(

std::unique_ptr<IProductProvider> product_provider,

std::unique_ptr<IStockProvider> stock_provider)

: _product_provider{std::move(product_provider)}

, _stock_provider{std::move(stock_provider)}

{

}

std::vector<ProductAndStock> get_all_products_in_stock() const

{

std::vector<ProductAndStock> result;

for (const auto& id : _product_provider->get_all_product_ids())

{

// We will not load products that are not in stock

const auto count = _stock_provider->get_stock_count_by_product_id(id);

if (count == 0)

continue;

result.push_back({_product_provider->get_product_by_id(id), count});

}

return result;

}

};

Assuming the product and stock information is available in a database, programmers can implement both interfaces and instantiate the Store like this::

Store store{

std::make_unique<DBProductProvider>(),

std::make_unique<DBStockProvider>()};

In the declaration above, it is assumed that DBProductProvider and DBStockProvider are derived from IProductProvider and IStockProvider, respectively, and that they implement all the pure virtual methods declared in their base classes. These methods should contain code that accesses the database, retrieves the information, and maps it to the data types specified in the interfaces.

Pros:

- The

Storeclass is completely agnostic about how the data is retrieved, which means low coupling. - Due to the reason above, the classes can be replaced with other ones very easily, and there is no need to modify anything in the

Store. - For the same reason, this makes creating unit tests very easy because creating

MockProductProviderandMockStoreProviderclasses is actually trivial.

Cons:

Not a “severe” negative point, but because everything is virtual here, polymorphism takes a little extra time for the actual bindings at runtime.

Alternative to Strategy Pattern: Policy-Based Design

Policy-Based Design is an idiom in C++ that solves the same problem as the Strategy Pattern, but in a C++ way, i.e., with templates ;)

Policy-Based Design involves having the consumer class as a class template, where the “Policies” (what was called “Strategy” in the Strategy Pattern) are part of the parameterized classes in the template definition.

The example above would look like this with Policy-Based Design:

struct Product

{

std::string id;

std::string name;

std::string brand;

};

struct Stock final

{

std::string product_id;

int count;

};

struct ProductAndStock final

{

std::shared_ptr<Product> product;

int stock_count;

};

template <

typename ProductProviderPolicy,

typename StockProviderPolicy>

class Store

{

ProductProviderPolicy _product_provider;

StockProviderPolicy _stock_provider;

public:

Store() = default;

std::vector<ProductAndStock> get_all_products_in_stock() const

{

std::vector<ProductAndStock> result;

for (const auto& id : _product_provider.get_all_product_ids())

{

// We will not load products that are not in stock

const auto count = _stock_provider.get_stock_count_by_product_id(id);

if (count == 0)

continue;

result.push_back({_product_provider.get_product_by_id(id), count});

}

return result;

}

};

To use it:

Store<DBProductProvider, DBStockProvider> store;

Pros:

- Better performance because all bindings are performed by the compiler, which creates a very optimized piece of code by knowing all the code in advance. Notice even that the

_product_providerand_stock_providerinstances are not even pointers! - Classes are still replaceable with other implementations, though not at runtime.

- It is also easy to create unit tests with this approach.

Cons:

- In my very specific example, no

IProductProviderorIStockProviderare defined because of the nature of templates. So the methods that need to be implemented must be documented somewhere. BUT, that can be solved through C++ Concepts, right? Thanks to C++ Concepts the validation that the providers implement all methods needed is done in compile time.

Something like this:

template <typename T>

concept TProductProvider =

requires(T t, const std::string& id) {

{ t.get_product_by_id(id) } -> std::same_as<std::shared_ptr<Product>>;

{ t.get_all_product_ids() } -> std::same_as<std::vector<std::string>>;

};

template <typename T>

concept TStockProvider =

requires(T t, const std::string& id) {

{ t.get_stock_count_by_product_id(id) } -> std::same_as<int>;

};

and then declare the Store as follows:

template <

TProductProvider ProductProviderPolicy,

TStockProvider StockProviderPolicy>

class Store

{

ProductProviderPolicy _product_provider;

StockProviderPolicy _stock_provider;

public:

Store() = default;

std::vector<ProductAndStock> get_all_products_in_stock() const

{

std::vector<ProductAndStock> result;

for (const auto& id : _product_provider.get_all_product_ids())

{

// We will not load products that are not in stock

const auto count = _stock_provider.get_stock_count_by_product_id(id);

if (count == 0)

continue;

result.push_back({_product_provider.get_product_by_id(id), count});

}

return result;

}

};

The static nature of this idiom makes it not a completely general solution, but it can cover, speculatively, a large percentage of cases. Sometimes, programmers think in dynamic solutions to solve problems that do not require such dynamism.